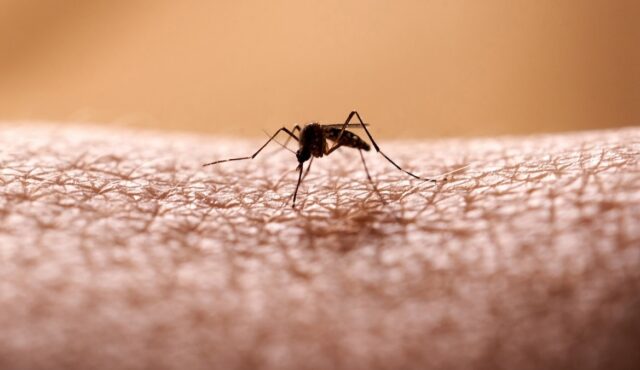

Mosquito-borne illnesses are on the rise—and we haven’t even reached peak mosquito season.

Over the summer, news of Dengue fever at the Paris Olympics sparked concern, but there are two other illnesses on the rise in the U.S. right now: West Nile virus and Eastern Equine Encephalitis (aka, EEE or Triple E). Both can only be contracted through the bite of an infected mosquito.

While still relatively rare, they’re not impossible to contract, and the illnesses can lead to severe complications for some. Recently, former director of the National Institutes of Allergies and Infectious Diseases, Anthony Fauci, MD, was hospitalized for six days after contracting West Nile virus, saying of his symptoms, “I really felt like I’d been hit by a truck,” per STAT News. And last week, a New Hampshire man died of Triple E, according to CBS. Additional cases have also been reported throughout New England, according to Today.

Why are mosquito-borne illnesses on the rise? It likely comes down to the ecology of the mosquito, William Schaffner, MD, a professor of preventative medicine and health policy in the division of infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University, tells Well+Good.

“We had a mild winter, so many of them weren’t killed. Then we’ve had a warming, which has extended geographic reach and life span of the mosquito population. We’ve also had a very wet season which gives mosquitos ample places to breed,” Dr. Schaffner adds. This is all a perfect recipe for increased mosquito population and infection, leading public health officials of some states to advise residents to stay indoors during dawn and dusk (when mosquitos are most active).

We know both are on the rise, but how different are Triple E and West Nile virus? And how likely are you to contract either? We spoke with a pathologist who specializes in vector-borne infections (aka, mosquito illnesses) and Dr. Schaffner about the differences between the diseases, and how you can best protect yourself.

What is West Nile virus?

Although not widespread, West Nile virus is the leading cause of mosquito-borne disease in the U.S., per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). It’s most commonly spread from bird to bird via mosquito bites, but humans can get it after being bit by infected mosquitos, too, per Dr. Schaffner. “West Nile virus is something that’s been endemic to the U.S. since around 1999, when the first cases of the disease were found in various states during the summer. This started mostly on the east coast and, over a period of four or five seasons, it moved west,” he says.

Cases typically rise around August and September—aka, peak biting season—and bites happen most often around dawn and dusk, when the mosquito population is high, according to Bobbie Pritt, MD, a pathologist and clinical microbiologist with a special interest in vector-borne infections at Mayo Clinic Laboratories.

When humans get West Nile virus, they are considered “dead-end hosts,” meaning the disease cannot be transferred from person to person, says Dr. Pritt. (The only outlier exceptions would be getting an organ transplant from an infected person, per Dr. Pritt, or if you’re a health care worker exposed to the open wound or injury of an infected person, per the CDC.)

What is Triple E virus?

Triple E stands for Eastern Equine Encephalitis. This rare-but-deadly mosquito-borne illness was first discovered in the 1830s in horses in Massachusetts (hence the name) and the first human case was identified in 1938, per The Center for Food Security and Public Health (CFSPH). Now, it’s most often found in North America and the Caribbean, and can infect horses, humans, and birds like ducks and emus. It most often circulates between mosquitos and birds in swamp environments, per the CDC.

Only a couple hundred cases of Triple E have been identified in the U.S. since 1964, with outbreaks most common in the late summer, per the CFSPH. Like West Nile, humans (and horses in this case) are considered “dead-end hosts.” Both humans and horses can develop severe disease and complications from this illness.

Where are they found, and how common are they?

In general, West Nile virus can be found throughout the U.S., while Triple E is more localized to the northeast and gulf coast states, says Dr. Schaffner. As of August 27, only 289 human cases of West Nile virus have been found across 33 states, according to the CDC. States with the highest number of cases include Texas, California, Pennsylvania, and New York.

“Meanwhile, there are only a few cases of Triple E reported each year,” according to Dr. Pritt. (The CDC says there’s an average of 11 annually.) This year, Triple E has only been reported in five states, including Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Vermont, and Wisconsin.

People who are at higher risk are those you might suspect—older individuals, those with underlying health conditions, or those who are immunocompromised, per Dr. Schaffner. You’re also more at risk if you work outside, travel to the tropics, or you’re a health care worker, per the CDC.

Symptoms of Triple E vs. West Nile virus

The symptoms of both West Nile and Triple E are very similar. “The time between the first bite to when you actually feel symptoms coming on could be a few days to a few weeks. It may just be a headache and mild fever, which goes away after a few days,” says Dr. Pritt.

About 70 to 80 percent of West Nile virus cases are mild, she adds. “You may just think “I must have had some type of bug,” and then you go back to feeling normal,” she says. Other mild symptoms of both include chills, body aches, joint pain, and other flu-like symptoms. Dr. Pritt says you may also get a rash of flat or raised lesions, called maculopapular rash. Often, these symptoms go away within a week or two.

That said, severe cases of Triple E and West Nile virus are a little different. Unlike the flu, which is an upper respiratory infection, mosquito-borne illnesses are systemic—meaning they can affect your entire body, especially your nervous system and neurologic function. Both can cause something called neuro-invasive disease, says Dr. Pritt. With West Nile virus, “about 1 percent develop neuro-invasive disease, where the virus goes into the brain or central nervous system,” she adds.

Both Triple E and West Nile virus can cause serious complications like meningitis (i.e., inflammation around the membranes of the brain and spinal cord), encephalitis (i.e., inflammation of the brain), or other long-term complications like difficulty walking, tying shoes or other daily tasks, mental and cognition issues, or even being bedridden, Dr. Pritt adds. While symptoms are similar, Triple E is more likely to cause severe disease.

Is one more deadly than the other?

While West Nile virus is more common and widespread across the U.S., Triple E is more dangerous. “I think of [Triple E] as the worse of the two,” says Dr. Pritt. About 30 percent of the people who get severe Triple E die, per Dr. Pritt and the CDC. This is different from the 1 percent of people who get severe disease from West Nile virus, of which “10 percent will die, and probably most of them will have long-term deficits,” says Dr. Pritt. These complications can range from cognition and mental issues to neurological and mobility difficulties.

Bottom line: Triple E is often more deadly than West Nile, and seems to be more of a threat to long-term health. And it doesn’t necessarily discriminate: While there are certain people at higher risk, Dr. Pritt says people in their 50s or younger could also be at risk of severe disease.

Treatment for Triple E vs. West Nile virus

Unfortunately, there is no cure or specific treatment for either of these mosquito-borne illnesses, says Dr. Pritt. If you get a severe case that requires hospitalization, health care workers will provide what’s called supportive therapies to help your body heal. According to Dr. Pritt, this may include a respirator to help you breathe better, or medications that help treat inflammation in the brain or meningitis. Because there are no vaccines or cure, it is essential that you protect yourself from mosquito bites in the first place. “Prevention is the key here,” says Dr. Pritt. (More on this below.)

How to protect yourself Triple E and West Nile virus

Mosquito bites may feel like no big deal, but both Dr. Schaffner and Dr. Pritt noted that the insects are some of the most deadly creatures in the world. When we see an uptick in mosquito-borne illnesses, preventing bites from happening in the first place is key. According to both Dr. Schaffner and Dr. Pritt, staying indoors during dawn and dusk can help cut down on exposure (although you can still get bit by an infected mosquito midday, they point out).

Other measures include wearing insect repellant when you go outside, especially if you’re near water or in heavily wooded areas, wearing long, loose clothing to protect your skin, and removing sources of standing water from around your home (i.e., birdbaths, old tires, buckets, or kids’ plastic toys that pool water after rainstorms, says Dr. Schaffner). If you’re planning to be outside for long periods of time—like going on a hike or camping—you can douse your clothes, boots, and gear in a substance called permethrin. It’s an insect repellant that can help prevent tick and mosquito bites, says Dr. Pritt.

When it comes to insect repellants in particular, Dr. Pritt suggests finding ones with 30 percent DEET, or using natural lemon eucalyptus oil repellants, which can work just as well as DEET. If you’re having trouble finding the right kind of repellant for you, the Environmental Protection Agency’s has an interactive page where you can explore the various types, ingredients, and how long protection with each lasts.

When to see a doctor

“This summer, we ask people not to think of [mosquitos] as a nuisance, but rather, a potential health hazard,” says Dr. Schaffner. “We ask people to take them more seriously.” While your chances of severe infection are rare, it is still possible to get these illnesses, especially if you live in an area where infected mosquitos have been identified. (You don’t have to be out in the woods; the mosquitos could be in your backyard, he adds.)

If you know you’ve been bit recently and begin to develop a fever, chills, fatigue, or headache that travels down your neck, see your doctor ASAP to rule out mosquito-borne illnesses. Your doctor can run tests to help differentiate between Triple E and West Nile virus (or other viruses), and get you the proper care you need.